I. New York and Hollywood

Pamela Moore wrote most of Chocolates for Breakfast during the summer of 1955. She was 17 years old at the time, working as a summerstock stage manager on Cape Cod Massachusetts. Her novel is the coming-of-age story of a girl named Courtney as she moves between an East Coast boarding school and her divorced parents in New York and Hollywood.

There are strong resonances between Pamela’s experiences as recorded in her letters and journals from that time, and scenes and characters in the book. Notes from her friend Valerie “Veigs” sound as if they could have been written by Janet, Courtney’s best friend in the novel. The diary entries of her meetings with Michael “Dandy Kim” Caborn-Waterfield read like sketches of the scenes with Anthony Neville in the Plaza hotel.

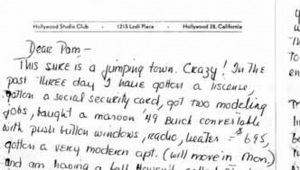

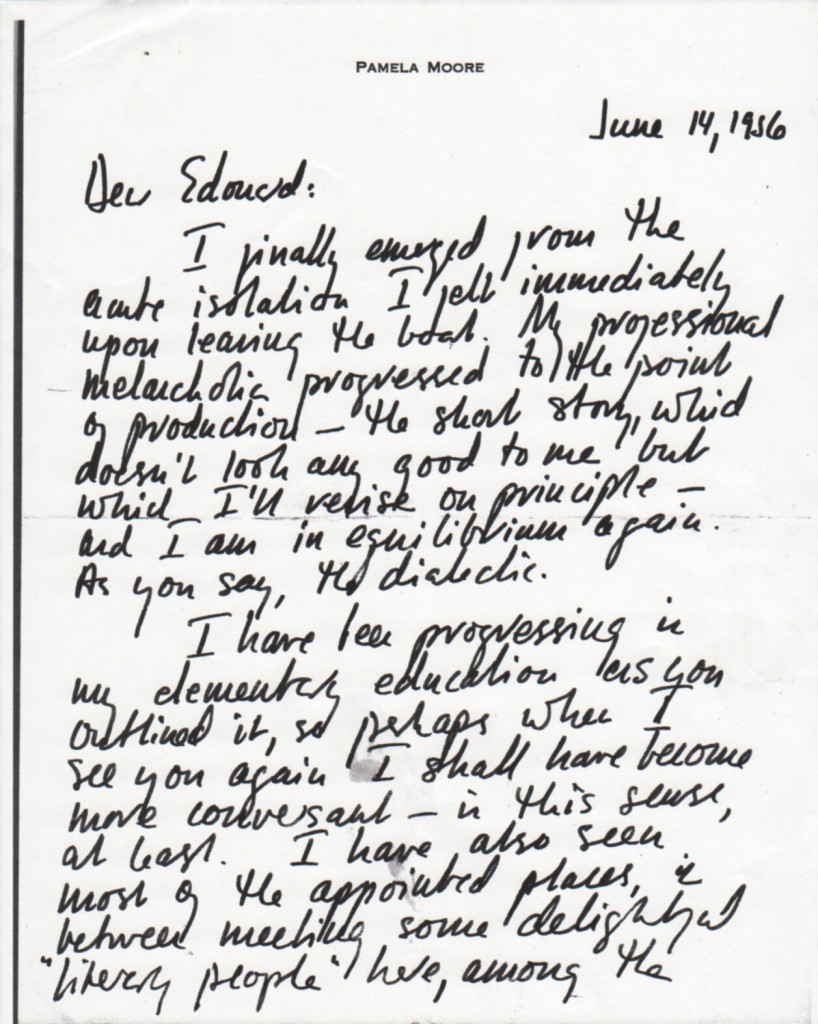

June 14th

Kim Caborn – Waterfield asked Val to bring me to meet him in his Plaza suite. He was wearing striped shorts and shirt tied at midriff, and had several days’ growth of beard. Then went to LI deb party with Buzz Henchly and Daphne Sellar and Val and others. Couldn’t think of anything but Kim. Back to Val’s at 7, woke up 1 hr late for Browns.

June 15

Kim called; picked me up at 5 in white coat, black stovepipe trousers, white french-cuff shirt, powder blue tie and white shoes. Sat in cab as he got white luggage from Plaza; went with him to apt. of their car dealer, 5 ave. at 954 (21)

“I want your mother to think well of me, Kim.”

Watched “Vie de Boheme” xxx xxx Kim got me home by 12, my deadline.

June 19

Remember man’s name and called Kim. He was worried about how we got the number. Said he’d been in country and was leaving next day for Bermuda.

It emerged only much later, when Dandy Kim became something of a celebrity through his business dealings, love affairs, and high-profile court cases, that his trips to Bermuda had in fact consisted of flights between Miami, Havanna, and various British colonial states in the Carribean — where only British citizens could purchase surplus arms from World War II.

II. Crossing to Europe, June 1956

Rinehart and Company bought Pamela’s novel in April of 1956, and the publication date was set for September of that year. With Rinehart’s $1000 advance, Pamela booked passage on an ocean liner from New York to England, en route to France.

On the way to Europe, Pamela Moore, now 18 years old, met Edouard de Laurot, age 34.

Laurot was a man of many identities: a film maker, writer, critic, and advocate of a politically engaged avant garde — le cinéma engagé. Laurot had recently co-founded Film Culture Magazine with Jonas and Adolfas Mekas. Laurot had worked on the set of Jonas Mekas’ film Guns of the Trees. He would soon begin directing Sunday Junction, an experimental film about America’s love of the automobile, set against the vast expanses of highways, shopping malls and gas stations.

After landing in England, Pamela writes a letter to Edouard, who has continued on to France. She tells him that she will be coming to Paris sooner than originally planned.

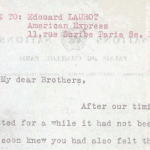

None of Edouard’s letters to Pamela survive. Many of his letters to the Mekas brothers contain instructions to destroy them, once his questions had been answered and his requests complied with. Pamela may have followed Edouard’s directives more scrupulously than others.

Oddly enough, the 1956 letter in which Edouard first announced to the Mekas brothers that he had met Pamela Moore, bears an unusual heading:

Keep my letters. Some things in the future may be needed for record.

III. The French ‘nouvelle édition’

That first week of meeting on the boat, Pamela and Edouard began outlining her next book. This became Prophets without Honor, her second novel, which would never published.

Soon after, they also began drafting new material to be included in the French edition of Chocolates for Breakfast, working out of a Paris hotel room over the course of several days.

The first French edition, published by Julliard in November of 1956, had been a straight translation of the text as published in the US just a few months prior. This French edition had already begun to appear in bookstores when Moore came to René Julliard with dozens of typewritten pages that she wanted him to include in the book. As Moore would later tell the story, René had at first refused, reportedly telling her “Pamela, even if you were my mistress, I couldn’t do this.” Eventually, however, he agreed.

Julliard released the second edition with the heading New Edition, Revised by the Author printed on the cover. This nouvelle édition omits entire scenes and stretches of dialogue from the original published version, and introduces a great deal of new material, including a preface about the kind of self-censorship (censure par anticipation) that Moore believed she had imposed on herself in the U.S.

What is the purpose of a preface? Apology? Explanation? Commentary? Indication of weakness or of bad faith—if it is written by the author—obligatory praise, perhaps, if the work of another. I never understood the purpose of prefaces, and I have little desire to write one. A note, nonetheless, is called for here.

The first French edition of my book was translated from the American version, which I never considered to be complete. I was in the United States at the time and it didn’t seem possible to me to bring out my book in its integral version. The possibility of publishing the latter was offered to me when I met my French publisher in Paris. Here then is the unexpurgated version.

Is that to say that the American version was subject to arbitrary alterations? Certainly not. It was rather a constraint that I imposed upon myself and which I would like to be able to name: a censorship by anticipation. This same constraint exists in the mind of many American writers who are conscious of the preferences of the audience about whom they are writing, and who also understand quite well how that audience is viewed by those that serve it. It is difficult for us to offer each reader the unvarnished truth, especially when it concerns the essential conflict that exists between the principles of our way of life and the demands of the human condition.

This conflict lies latent in all the hearts in our country, and torments many of us. We turn away from this terrifying truth with what I would term a kind of collective bad faith*. This is what led me to express myself with some reticence in the course of my initial work. But after having reflected on it, I felt obliged to try to arrive at the causes of this moral crisis that so afflicts the youth whom I describe in this book.”

P.M.

* Mauvaise foi commune: communal bad faith, collective false consciousness or lack of integrity.

Here Pamela transcribes a review from L’intransigeante in a letter to Edouard. The review was written by a French critic who had evidently read both the original and revised French versions. Adieu Fraicheur (Farewell Freshness) a pun on the title of Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristess (Hello Sadness).

I received a letter from Odette Arnaud saying “Les journaux parlent maintenant de votre nouvelle édition. Certain y mettent l’incorrigible ironie que vous avez deja constaté des journalistes de chez nous.” Enclosed was a piece (two paragraphs) from l’Intransigeant: “Adieu Fraicheur . . Miss Moore has learned by her stay in Paris that Burgundy is not an aperitif, Mr. Neville now drinks champagne. . . the changes all come to one point: the heroine has set herself to thinking. Now she walks to the window and says, “I see here a country where only misery and injustice thrive.”

Julliard, give us back the gauche freshness of the original version!”

Laurot’s military, even aristocratic bearing, his sense of participation in history and tales of combat and political intrigue, all must have made a deep impression on an 18 year old American who had just emerged from the world of prep schools and Ivy League dissolution.

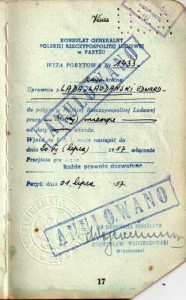

Pamela fervently enlisted in his causes, which included the production of Sunday Junction, Laurot’s experimental film about cars, highways, suburbia and American culture. Moore purchased or smuggled into France cameras, film stock, even a car. She drove Laurot to Stockholm and Switzerland, ran errands for him, and awaited his return in various border towns. His work including writing about current trends in cinema, promoting various films, festivals, and Film Culture magazine – in the Soviet-controlled East as well as Western Europe. De Laurot’s passport shows several forays behind the Iron Curtain between the years 1956 – 58, into Poland and East Germany.

IV. After Chocolates

Back in her mother’s apartment in NYC, between European sojourns, Pamela would listen to records of the Red Army Chorus, and write to Edouard about how alienated she felt from the world she had grown up in.

Some time around 1958, mutual friends introduced her to Adam Kanarek, a Polish-Jewish refugee who had survived the Holocaust in hiding, and who was now working in the Slavonic Division library of Columbia University.

Adam and Pamela began corresponding during the periods when she was in Europe. She exhorted him to be more politically active, to embrace a philosophy of commitment and engagement in history. Kanarek once responded that, having witnessed both the Nazi genocide and the Soviet occupation, he was himself skeptical of all ideologies and their calls to action.

Pamela Moore and Adam Kanarek were married in 1958. During the six years of their marriage, Moore finished three more novels: The Exile of Suzy Q, East Side Story (AKA The Pigeons of St. Mark’s Place) and The Horsy Set, but none of these were to prove as successful as her first book. Her husband Adam was at first her loyal champion and her guardian knight, protecting her from the threats of the outside world, ensuring that she might have the privacy and sheltered space in which to write.

Chocolates for Breakfast, which Pamela had written at age 17, includes an episode of severe self-cutting and the suicide of the heroine’s best friend. Both of these events are shown as having a cleansing, redemptive effect, chastising the grown-ups and reminding them of their responsibilities. It is a very young person’s view of suicide as a means of somehow making things right again, a view that Pamela may not have ever outgrown.

|

The staff at Rosemary Hall, the boarding school on which Pamela Moore based the fictional Scaisebrooke. Carolyn Swift was the model for the kindly teacher Miss Rosen in the novel.

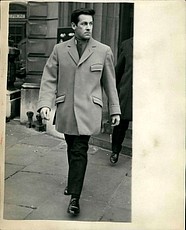

Dandy Kim Waterfield, seen leaving a courtroom in several years later, when he was accused of robbing the safe of film mogul Jack Warner’s house in the Riviera.

Left to right:Pamela Moore in a trenchcoat and sunglasses on a pier; a car unloading from a ferry; a ship at dock. Strip of negatives found in Jonas Mekas’ archives.

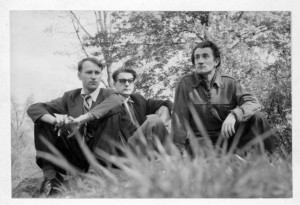

Left to right: Jonas Mekas, Adolfas Mekas, Edouard de Laurot

From Edouard de Laurot to Jonas and Adolfas Mekas:

There were some worth while people on board; among them the American Françoise Sagan (but a deeper person) an 18 year old girl writer whose first book is being published and who traveled on the advance money. She became first interested then engrossed in our ideas and I have little doubt her next book (which we started outlining together) will at least bear visible traces of our encounters.

. . . I am in equilibrium again. As you say, the dialectic.

I have been progressing in my elementary education as you outlined it, so perhaps when I see you again I shall have become more conversant.

Pamela Moore in Paris, Aug. 1956, just before the publication of Chocolates in the US.

The French Nouvelle Édition,

Nov. 1956

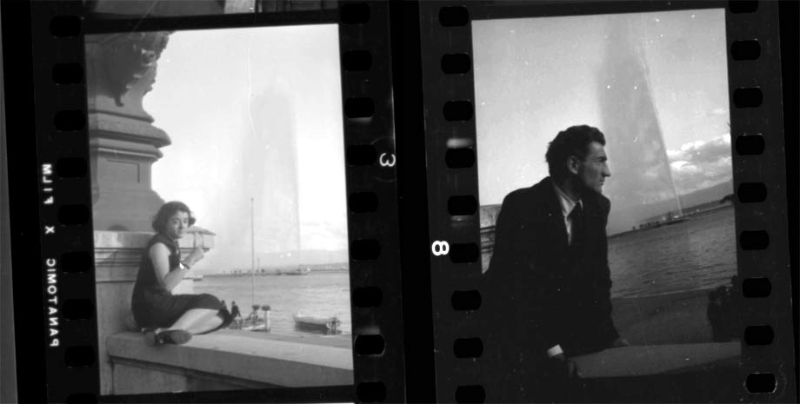

Pamela & Edouard, Geneve, ca 1957

Military decoration Odznaka za Rany i Kontuzje,found among the photographs of Pamela and Edouard in Mekas’ archives.

De Laurot’s visa into Communist Poland,

annulled, 1957

Adam Kanarek reading Kultura magazine photograph by Pamela Moore

|