I. Boarding School, Hollywood, & New York CityPamela Moore wrote most of Chocolates for Breakfast during the summer of 1955. She was 17 years old at the time, working as a stage manager for a summer stock theater company. The events and characters depicted in the novel are roughly parallel in Pamela’s life in the two years leading up to then as a girl of 15 and 16, going back and forth between Rosemary Hall, Los Angeles, and New York City. Notes from Pamela’s friend Valerie “Veigs” sound as if they could have been written by Janet, Courtney’s best friend in the novel. The diary entries of her meetings with Michael “Dandy Kim” Caborn-Waterfield in 1953 read like sketches of the scenes with Anthony Neville in the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan:

As emerged only later, when Dandy Kim became a celebrity in the UK through his business dealings and high-profile court cases, those trips to Bermuda had included runs between Miami and Havana as well — Bermuda in 1953 being a Crown colony still under British rule, where the holder of a British passport and a pilot’s license might freely purchase surplus arms from World War II. In interviews and journal entries, Pamela expressed surprise and frustration that people mistook her for the character of Courtney. She herself had only been a chronicler of this high society world of decadence, describing rather than endorsing it; she was much more of an observer and outsider than she had made Courtney to be. Janet Parker was possibly a composite character of several of her friends and classmates, including Valerie “Veigs” Veigel. However none of them took their own lives, as Janet does in the novel. Pamela’s mother Isabel Moore was a writer, not an actress, but Isabel’s career did veer from extravagant heights to hardscrabble lows: from being an editor of Photoplay magazine and confidante of screen stars in the 1930s and 40s, to churning out over a dozen paperback titles in later years under various pseudonyms. Isabel Moore did live for a time at the Garden of Allah in Hollywood, and was in fact evicted for non payment of rent; all her clothes and other belongings were impounded, and she was never able to reclaim them. However it was her older daughter Elaine, Pamela’s half-sister, who actually lived there with Isabel, and whose own belongings were lost along with her mother’s. |

|

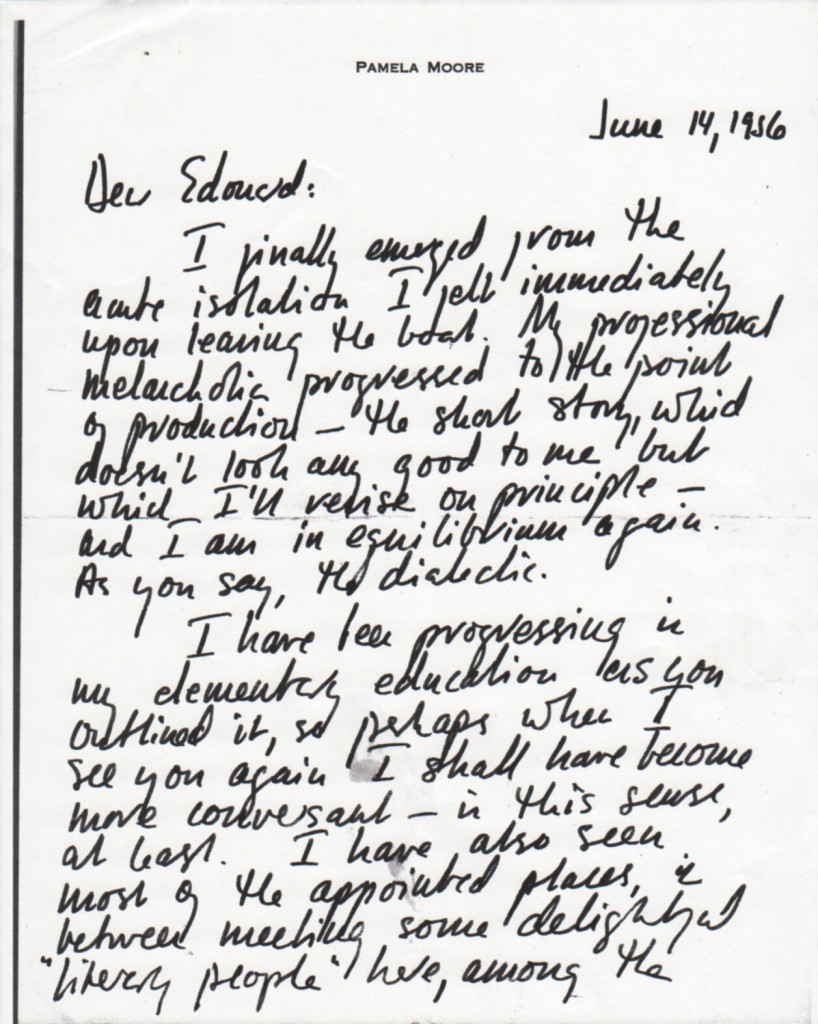

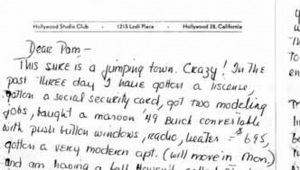

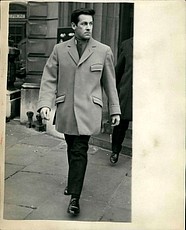

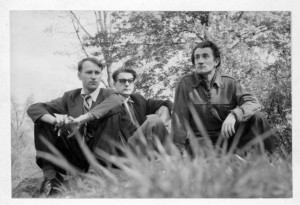

II. Crossing to Europe, June 1956Rinehart and Company bought Pamela’s novel in April of 1956, and the publication date was set for September of that year. With Rinehart’s advance, Pamela booked passage on an ocean liner from New York to England, en route to France. On the way to Europe, Pamela Moore, now 18 years old, met Edouard de Laurot, age 34. Laurot was a man of many identities: a film maker, war hero, writer, critic, and advocate of a politically engaged avant garde — le cinéma engagé. He had recently co-founded Film Culture Magazine with Jonas and Adolfas Mekas, and had worked on the set of Jonas Mekas’ film Guns of the Trees. Laurot would soon begin directing Sunday Junction, never finished, an experimental film about America’s love of the automobile, set against the vast expanses of highways, shopping malls and gas stations. After landing in England, Pamela writes a letter to Edouard, who has continued on to France. She tells him that she will be coming to Paris sooner than originally planned. None of Edouard’s letters to Pamela survive. Many of his letters to the Mekas brothers contain instructions to destroy them once his questions had been answered and his requests complied with. Pamela may have followed Edouard’s directives more scrupulously than others, or destroyed them for reasons of her own. That first 1956 letter, in which Edouard announces to the Mekas brothers that he has met Pamela Moore, bears an unusual heading:

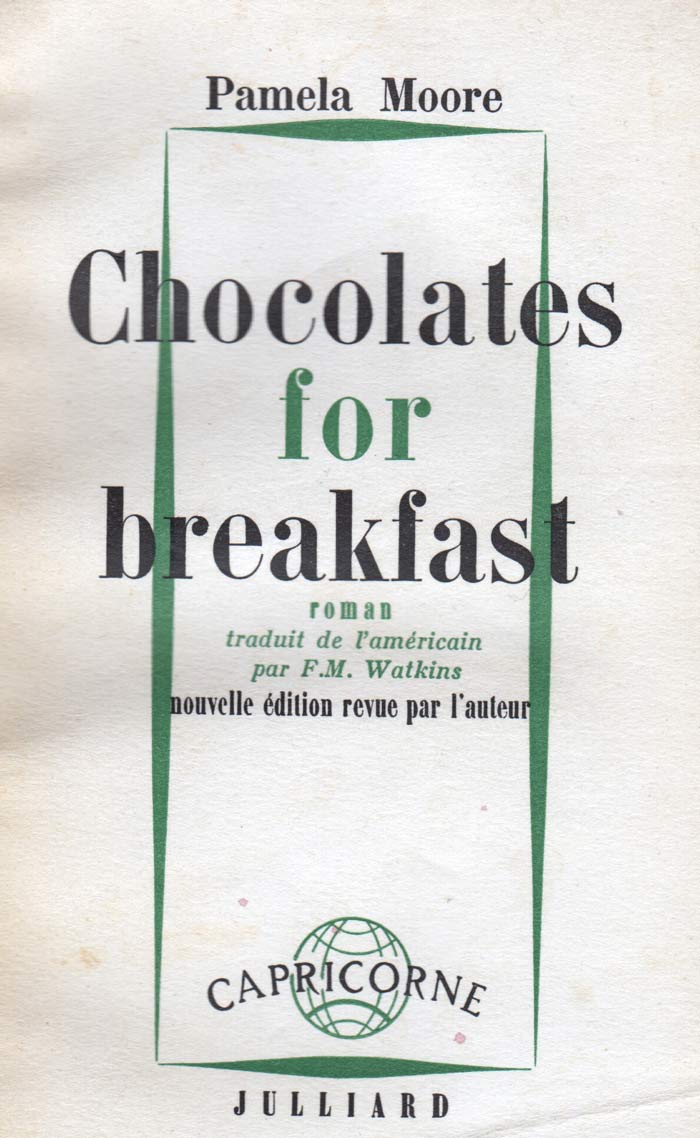

III. The French ‘nouvelle édition’That first week of meeting on the boat, Pamela and Edouard began outlining her next book, which eventually became Prophets without Honor, her second novel, never published, although her new agent Sterling Lord had sold it to Alfred Knopf on the basis of Pamela’s outline and synopsis. Working out of a Paris hotel room over the course of days and weeks, Pamela and Edouard also began drafting new material to be included in the French edition of Chocolates for Breakfast. The first French edition, published by Julliard in November of 1956, had been a straight translation of the text as published in the US just a few months prior. This French edition had already begun to appear in bookstores when Moore came to René Julliard with dozens of typewritten pages that she wanted him to include in the book. As Pamela would later tell the story, René had at first refused, reportedly telling her “Pamela, even if you were my mistress, I couldn’t do this.” Eventually, however, he agreed. Julliard released the second edition with the heading “New Edition, Revised by the Author,” printed on the cover. This nouvelle édition omits entire scenes and stretches of dialogue from the original published version, and introduces a great deal of new material, including a preface about the kind of self-censorship (censure par anticipation) that Moore believed she had imposed on herself in the U.S.

* Mauvaise foi commune: communal bad faith, collective false consciousness, lack of integrity. In a later letter to Laurot, Pamela transcribes a review from L’intransigeante by a French critic who had evidently read both the original French edition and the revised nouvelle édition:

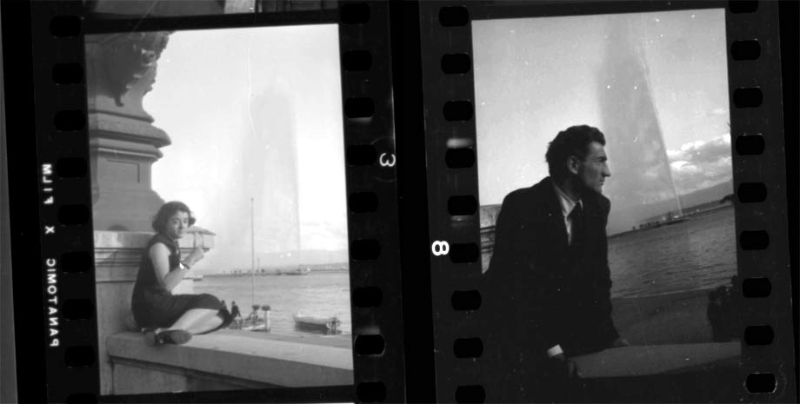

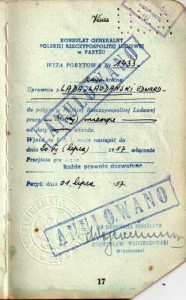

* Adieu Fraicheur (Farewell Freshness), yet another pun on the title of Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse (Hello Sadness). Laurot’s military, even aristocratic bearing, his sense of participation in history and tales of combat and political intrigue, all must have made a deep impression on an 18 year old American who had just emerged from the world of prep schools, Hollywood film types and Manhattan drinking establishments. Pamela fervently enlisted in his causes, which included the production of Sunday Junction, Laurot’s experimental film about cars, highways, suburbia and American culture. Moore purchased or smuggled into France materiel including cameras, film stock, even a car. She funneled most of her earnings to Laurot, drove him to Stockholm and Switzerland, ran errands for him and awaited his return in various border towns. Laurot’s work involved promoting various films, festivals, and Film Culture magazine, throughout Western Europe and in the Soviet-controlled East as well. Laurot’s passport shows several forays behind the Iron Curtain between the years 1956 – 58, into Poland and East Germany. |

— undated letter ca. June 1956, from Edouard de Laurot to Jonas & Adolfas Mekas

— from Pamela Moore to Edouard de Laurot, first letter, dated June 14 1956

Laurot’s visa into Communist Poland, annulled, 1957 |

IV. Book becomes bestseller, author chooses exileOn occasional trips back to the US, staying in her mother’s apartment in New York City, Pamela would listen to records of the Red Army Chorus, and write to Edouard about how alienated she felt from the world she had grown up in. From Europe, she would write her new literary agent, Sterling Lord, sometimes requesting him to send money to her in Paris. Although Sterling had not been Pamela’s agent when she sold Chocolates to Rinehart, he did broker the sale of the book’s paperback and film rights; as well as the sale to Alfred A. Knopf of Moore’s second novel, Prophets without Honor. Chocolates was gradually becoming a bestseller in France as well as in the US, with well over half a million paperback sales in the US by April 1958. Still, Sterling sometimes had to remind her that she had already received all payments due to date. Later in 1958, mutual friends introduced Pamela to Adam Kanarek, a Polish-Jewish refugee who had survived the Holocaust in hiding, and who was now working in the Slavonic Division library of Columbia University. Pamela and Adam began corresponding during the periods when she was in Europe. She exhorted him to be more politically active, to embrace a philosophy of commitment and engagement in history. Kanarek once responded that, having witnessed both the Nazi genocide and the Soviet occupation, he was himself skeptical of all ideologies and their calls to action. Pamela Moore and Adam Kanarek were married in 1958. During the six years of their marriage, Moore finished three more novels: The Exile of Suzy Q, East Side Story (AKA The Pigeons of St. Mark’s Place) and The Horsy Set, but none of these were to prove as successful as her first book. Her husband Adam was at first her loyal champion and guardian from the threats of the outside world; threats real and imagined, including Laurot and his henchmen; protecting her privacy, and creating a sheltered space in which she might write. Courtney in Chocolates for Breakfast, after first lover leaves her, deliberately cuts the skin at the joints of her fingers, an act which provides some relief from her sense of guilt and sadness, and lands her in a sanitarium. The suicide of her best friend Janet, later in the novel, can likewise be seen as having a similarly cathartic, even redemptive effect, chastising the grown-ups and reminding them of their responsibilities. |

Note from Sterling Lord to Pamela Moore April 1958  Adam Kanarek reading Kultura magazine photograph by Pamela Moore |

V. Cioccolata a colazioneThe Italian edition of Chocolates for Breakfast figured prominently in an obscenity trial that took place in Italy from 1960 through most of 1964. The defendant was Alberto Mondadori, CEO of the largest publishing house in Italy. The two other books named in the the case were the translations his company had published of Jack Kerouack’s “Subterraneans” and D.H. Lawrence’s “Lady Chatterley’s Lover.” Technically, the charge was violation of article 528 of the penal code, oltraggio al comune senso del pudore: crimes against common decency. This law allowed for exceptions in the case of works of art — meaning that, according to the logic of obscenity laws, if a work can be proven to be art, then it is not obscene. Notable Italian writers of that era — such as Anna Banti, Richard Bacchelli, and possibly Giacomo Debenedetti — testified in defense of the artistic value of Cioccolata, citing the serious and tragic mood of the novel, and the fact that it was “without any doubt sincerely moral.” Another factor considered in the case was Moore’s recent suicide, “evidence of her problematic nature, of her being a serious writer.” The trial might be seen as a kind of long drawn-out morality play, a witch hunt, a karmic or clerical or bureaucratic process from transgression to judgement and ultimate absolution. In October of 1964, the judges delivered a verdict of Not Guilty. Alberto Mondadori was acquitted. After being banned for the duration of the trial, Cioccolata a colazione returned to bookstores throughout Italy at the end of 1964. Within 2 years, over 400,000 copies had been sold. The book remained a best seller in Italy through most of the 1960’s, and stayed in print there for over 40 years, longer than in any other country. And until the summer of 2014, when Mondadori reissued the novel in a new translation of the US edition, the only version available in that country had been based on the heavily revised text of the French nouvelle édition. It had been a gift, to her new lover, from a young woman very much in love.

VI. PosterityMoore’s philosophy professor at Barnard, Joseph Gerard Brennan, included in his memoirs a reminiscence of his student, Pamela Moore:

For nearly forty years following her death in 1964, Pamela Moore was mentioned rarely in print, other than the inclusion of her novel in lists of early lesbian fiction: in a 1965 article entitled “Feminine Equivalents of Greek Love in Modern Fiction,” Marion Zimmer Bradley, who later wrote the best-selling Mists of Avalon, compares Chocolates for Breakfast favorably with several novels about the obsessive love of a young girl for an older woman. Bradley concludes:

In her book Contingent Loves: Simone de Beauvoir and Sexuality, Melanie Hawthorne surveys French novels that feature an erotic bond between schoolgirls and older female teachers, and cites Chocolates for Breakfast among the English language counterparts to this genre. Had the pages cut from the original manuscript left behind some kind of trace? These cuts may have been the result of censorship, self-censorship, mauvaise foi, or the editing process of paring a book down its most suggestive, essential form. In any event, the missing material might be sensed though not seen:

Or as if a face were cropped from a photograph in such a way that some might still perceive it to be there: a faint outline, a ghost image of original love and loss. |

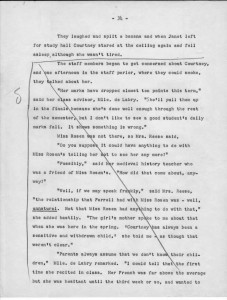

The Trial* A passage from “Chocolates for Breakfast” that may have prompted the obscenity charge was this exchange between Courtney Farrell and Anthony Neville:

One of the three judges wrote in his decision:

* Description of the trial and quotes from the transcripts courtesy Antonio Armano, author of Maledizioni: Processi, sequestri, censure a scrittori e editori in Italia dal dopoguerra a oggi, Nino Aragno Editore, 2013.  Italian translation 18th edition,1966

Excerpts from the Miss Rosen speaks:

Courtney to Anthony:

|

VII. The Original US typescriptIn their published version, Rinehart cut roughly a dozen pages from the typescript that Pamela Moore had submitted in April of 1956, under her original title “Everything Happens in September.” These deleted pages bear little resemblance to the revisions of the French nouvelle édition. The connection between Courtney and Miss Rosen is evoked as a kind of refrain throughout the novel: however it is described in sensual, not philosophic terms:

Courtney watching Barry, her first lover, as he sleeps:

The original typescript of Chocolates for Breakfast includes 3 pages at the end that were cut from the published version. After leaving Anthony, Courtney goes to meet Charles at Sardi’s. They drink a toast to enchantment. Then, trying to make sense of Janet’s death, Courtney says:

|